How to buy art in the primary market

Most people buy art when it’s sold for the first time, but you still need to do your homework.

Hello and welcome to the latest edition of the Priceless newsletter, which is brought to you after a …. significant interlude. Writing that pays the bills keeps getting in the way of this free newsletter, but I’ve finally got some time to bring you a fresh installment. On the bright side, none of my long-suffering subscribers can accuse me of bombarding them with emails. I’ll endeavor to bug you all much more consistently in the future.

This newsletter is all about providing an unvarnished view of the art market, and what to consider when you’re buying art. One of the very best ways to do that is to tap the knowledge of collectors who have been buying art consistently for decades, and have already seen it all.

Last week, a panel in New York hosted by Artlogic, a platform solution for art businesses, explored the relationship between art collectors and art dealers. One of the panelists, Rodney Miller, vice chairman at JP Morgan and a collector of modern and contemporary Black artists for 25 years, had some excellent advice to give about this art buying business.

He described his time as an art collector, which began with him buying art on layaway, as a constant learning experience of talking to galleries, talking to other collectors, talking to artists, and finding out about their peers. This enabled him to collect art that was undervalued both from a cultural and financial perspective at the time. “When I first saw Norman Lewis, he was nobody, and William T. Williams didn't have a gallery,” he said, mentioning two household names today. “I focused on those abstractionists at the time because their work really stood up very well to their peers.”

Rodney Miller (far right) and Roselyn Mathews (center) at Artlogic’s panel last week. Credit: Artlogic.

Roselyn Mathews, a younger collector and a vice president at Lucifer Lighting, said she was still figuring out the art market, which she described as “a really mysterious industry”. She recommended that new art collectors visit artist residency programs, such as Silver Art Projects and Pioneer Works in New York City. “It's an incredible opportunity to get in touch with artists that you've never heard about and to develop personal relationships with them,” she said.

She also described her strategy for dealing with a softer art market right now, particularly for contemporary art. “I look at art investment like any other investment in a down economy. I want to do my due diligence…and I want to understand the comps.” She says that current market conditions sometimes mean that galleries and dealers are prepared to offer a discount on artworks, or offer collectors something that wasn't previously available to them.

Price disparities

As both Miller and Mathews suggest, researching artists and their body of work before you buy art in the primary market (when it’s sold by galleries and dealers for the first time) is particularly important. It can definitely go both ways, but an artist’s primary market prices can sometimes be higher than prices in their secondary (or resale) markets.

That may not be such a big deal if you intend to keep your artwork forever, but buying art that is new to the market with the assumption that you’ll be able to sell it for a profit at some point is a mistake.

I’m not talking about the 90% of art that devalues the moment you leave the gallery, a memorable stat offered by an art adviser I once interviewed. I’m referring to artists that are already coveted by the art market. As I’ve written before, so-called wet paint contemporary art, particularly newly created works by sought after ultra- contemporary artists, often have a volatile price history in the secondary market, and demand ebbs and flows. Overall, it’s currently at an ebb. Between 2022 and 2023, total auction sales of work by ultra-contemporary artists (those born after 1974) fell 26%, according to Artnet’s The Intelligence Report.

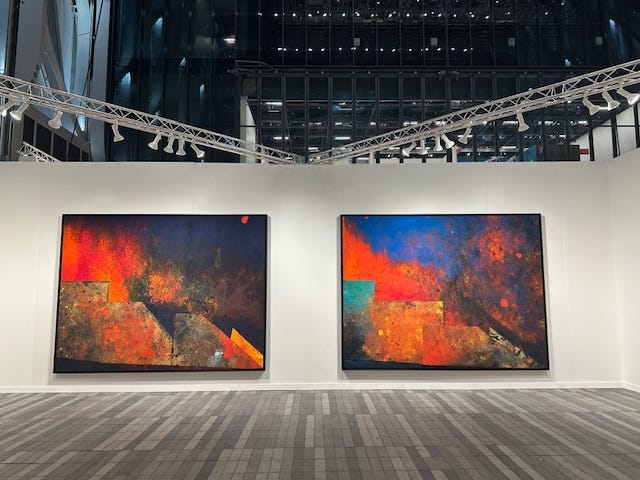

But works by highly successful, established artists like Sterling Ruby can also sell for less in the secondary market. As Katya Kazakina reported in Artnet, four enormous, fiery, vibrant paintings from Ruby’s Turbine series sold at Gagosian’s booth Frieze New York last week for $550,000 each, but only one of Ruby’s works has been resold at auction for more than that amount since 2018. Next week, Christie’s will auction an even bigger Ruby canvas in New York, titled SP113, which has an estimate of $250,000 to $350,000. That’s a pretty big disparity between Ruby’s primary and secondary market.

Two works from Sterling Ruby’s Turbine series, taken at Gagosian’s booth on my trip to Frieze New York last week.

This is not just an issue when buying in the primary market, because prices can also be unpredictable even if you are buying artworks previously owned by other collectors. The art market is full of examples of artworks that have been resold more than once at auction for dramatically different prices. Just last month, as Karen Ho reported in ARTnews, Jamian Juliano-Villani’s West End Girls sold at Sotheby’s in Hong Kong for HK$139,700 ($17,829), when back in 2020, the same painting sold for $118,750 at a charity auction in New York.

A lack of transparency

But the disparities between prices in the primary market and the secondary market are harder to unearth, because, unlike auction houses, which resell art, most galleries and dealers operating in the primary market don’t make the prices of the art they sell publicly available.

That’s beginning to change, but this lack of transparency means that finding price comparisons in the primary market can be tricky. As Melanie Gerlis wrote in the Financial Times recently, “Persistent opacity around issues such as prices, ownership and condition reveals the limits of [an art] market with no overarching oversight, and which still often relies on handshakes and hidden codes of conduct.”

So how do you do your research when buying brand new art? Certainly, checking if the artist has a resale market on data platforms like Artnet or Artprice, and looking at prices there, is a good first step. Other platforms are trying to provide more information on prices in the opaque primary market. Limna, for example, is an AI-assisted platform that provides art buyers with immediate price estimates, drawing on its extensive database of primary market sales at galleries and exhibitions.

But, as Miller and Mathews pointed out during last week’s panel, there’s no substitute for talking to artists, learning about their body of work, and talking to the gallery that represents them. After all, as they both stressed, forging those connections and constantly learning are a huge part of what makes collecting art so fun and rewarding in the first place.

With that, I’ll leave you with my top art investment news picks below. This is a free newsletter, so I’d love it if you could subscribe, if you haven’t already, and share this with others.

Finally, if you’d like to make a small donation to help me get this newsletter out into the world, I’d be very grateful. You can do so at buymeacoffee.com. Thank you and thanks for reading!

News in brief

Global art market sales decreased 4% in value in 2023 to an estimated $65 billion, according to the 2024 Art Basel and UBS Global Art Market Report, published in March, with high interest rates, inflation and political instability causing a slow down at the top end of the market. The good news is that the report also found that sales volumes were up in 2023, particularly for lower priced works.

In the next major test of how the art market is faring, an estimated $1.2 billion of art will be auctioned off at Christie’s, Sotheby’s and Phillips in New York next week, including works by Tracey Emin, Brice Marden and Julie Mehretu. The top lot, by estimate, is Untitled (ELMAR), a 1982 Jean-Michel Basquiat painting with an estimate of $40 million to $60 million.